This post is a reprint of a post by L.L. Barkat

that originally ran at Tweetspeak Poetry

at the strange beginning of the 2020 pandemic.

Humanity happens.

That’s why I almost didn’t write to you today. It’s also why we made our own “coffee shop” down by the Hudson River this afternoon, where the sun was warm enough to keep the 53-degree chill at bay.

Making a coffee shop is easier than you think, especially if your standards for imbibing don’t include coffee. We brought Ceylon tea, with a touch of cardamom. And tea sandwiches of an experimental nature.

The dandelions are just poking up out of the ground here in New York, where the new deal is social distancing, to keep the coronavirus from overtaking whole communities. College was closed. So, we made our own popup coffee shop down by the river. As for the dandelion leaves, we used them in our tea sandwiches, which also had a generous layer of fresh garlic, marinated in olive oil with red pepper flakes, made all the more healthy by a dash of oregano oil.

My daughter’s college is doing their own experiment—with virtual learning. By 6 pm Friday, she will know what the rest of the semester holds. Of course she doesn’t want to spend the next few months studying from home. That’s not what she signed up for.

But then, none of us sign up for what our fragile humanity sometimes hands us.

At the river today, we drank our Ceylon, ate our tea sandwiches, and then had whole-wheat lemon cookies we’d made last night, knowing we’d be going to the river this afternoon. Or hoping we’d be going. We did.

There was a little boy who came up onto the gazebo stage where we’d made our coffee shop. He sang like there was no such thing as fragility in the world. He cut a few dance moves that left us chuckling. When he was finished with his show, we clapped heartily as he stepped down the stairs to go on his way with his mom. Then we read a few poems from Earth to Poetry and Where the Sidewalk Ends. We decided that Shel Silverstein has a side to him that sees deeper than you might think. Sees the humanity. Sees the fragility.

When life feels fragile, it is good to have a sense of connection beyond your immediate circumstances. One way we provide this in our Every Day Poems deliveries is to occasionally include older poems. Recently, we sent “The Red Wheel Barrow” to subscribers. You might think “The Red Wheel Barrow” has nothing new to say to us. You might be right. That is okay.

Tonight, as I type, I am sitting in my grain-gold living room, with its old red-oak floors, French doors to my left that open to the dining room, and dark wood trim everywhere. In the corner is a secretary I bought this summer. I’d been needing some kind of storage furniture for a very long time, and I’d been saving towards a new piece that I’d seen in a catalog. But then I thought about it: why not get something with a history instead? So I went to Melita’s and found a reasonably-priced piece that she’d rescued from Portugal and refurbished. I don’t know what kind of wood it is. She didn’t either. But it’s beautiful. And the lock in the doors at the bottom is from London, long ago.

I love the feeling of comfort that old wood seems to give. There’s a simplicity to it that’s also quite rich. Like “The Red Wheel Barrow.”

This poem was written by William Carlos Williams, who was a physician. He must have encountered the fragility of life every single day. And he met that fragility with a poem like this one, which gives us what feels like an image frozen in time—yet timeless, infinite. The red, the white, they are life colors. One that rushes in, the other that fades out. In their way, the colors alone in this poem have a sense of being parts of a whole that keeps shifting. Like the cycles of life.

My eldest daughter volunteered at a farm last year, and she was often transporting things in wheel barrows and carts, especially over to the chickens, who eagerly waited for the vegetable scraps she might be sharing. When she wasn’t pushing wheel barrows or pulling carts, sometimes she was gathering eggs. It was a virtuous circle where, in essence, she and the chickens gave to each other. “The Red Wheel Barrow” contains this virtuous circle without saying a thing about it. The “glazed with rain water” status of the barrow only adds to the sense of circularity and cycles. Without rain there is no life. And the rain itself is part of a cycle.

In another poem we ran recently, Ezra Pound says to Walt Whitman, “We have one sap and one root—”. He says this after admitting that he did not originally see the way he and Whitman were connected. Maybe Pound had come across some fragility of his own, since he’d finally become “old enough.” And, through that experience, perhaps he could see how poetic history connected them.

Making it a priority to run older poems in Every Day Poems is our way of connecting readers to the rich past of poetry. It’s a past we can turn to when we feel our fragility. It connects us through time, with others who’ve gone before us, walked in the rain that now glazes our windows on stormy days.

***

The Red Wheelbarrow

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

— William Carlos Williams

***

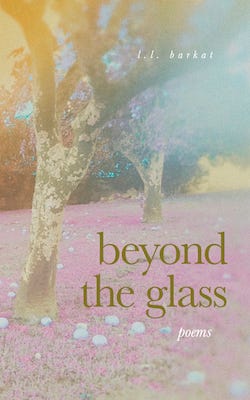

L.L. Barkat is the author of twelve books, including The Novelist: A Novella; Rumors of Water: Thoughts on Creativity & Writing (twice named a Best Book of 2011); and Love, Etc. Her poems have appeared at Every Day Poems, Best American Poetry, VQR, NPR, and the BBC.

Featured photo by Patrycja Jadach, Unsplash license.

Beautiful post. We are living through another perilous time. This post feels especially meaningful to me tis morning.